Janet

I immediately found our language to be a barrier. Janet excitedly responded to each of my questions but often ideas were lost in translation or cultural impediments. I was a young, assertive Westerner, while Janet was from a quieter more guarded generation, a practitioner of blind faith, hard work, and frugality. Still, her information was forthcoming, and though not always well explained, nevertheless delivered with gusto and commitment to assisting me.

It was quickly apparent that, like so many of my expectations regarding my African assumptions, times were changing. The world and customs in which Janet had delivered her babies was very different than the ways her grandchildren were coming into being. Today women went to the clinic or hospital to deliver. In her day birthing in the village was the norm. She explained the reasoning:

We were suffering because the babies didn’t have IDs and we didn’t know when they were born. They couldn’t go to school without an ID. Now they are born in clinic to get ID.

It struck me that I had very different reasoning regarding clinic births compared to Janet. My immediate assumption was that women were encouraged to use the clinics as a step towards safer births, for lowering infant mortality. Yet, Janet saw it as a government ordinance, a reflection of their attempt to control.

I was curious about exactly how women got to the hospital when they went into labor. Many villagers rely on taxis as a means of transportation and often they can be sporadic and don’t run at night.

Oh, when it’s time someone must find a car. Sometimes babies are born in the car because they are too late.

Yet, in Janet’s day this was not the case. When it was near time women would prepare water and traditional medicines from the garden, “not white medicine.” When women felt “the pains” they would walk in the village to help the baby to come. Eventually she would deliver the baby while kneeling.

In the hospital you lay in a bed but at home we squatted.

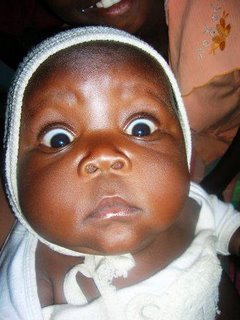

After the baby was born, and the following still happens even today, the woman and the baby went into seclusion until the umbilical cord “was dry.” During this time the husband can be shown the baby, but he does not sleep with the wife. Instead, the new mom sleeps with her mother, if unmarried, or with her mother-in-law if married. In fact, even the new mother’s older counterpart, the infant’s grandmother, does not sleep with her husband during this period.

I moved the conversation backwards on the time spectrum in order to gain Janet’s views on conception and pregnancy.

The day man makes you pregnant, you feel somehow, you know.

How do you feel while you’re pregnant? Do you still work?

Sometimes you love your husband very very much and you don’t want him to go to work but sometimes….eish….you hate husband. We still work when pregnant, very hard and we are always vomiting and tired.

What happens if the mom gets sick?

She goes to witch doctor for traditional medicine

What happens if there is something wrong with the baby?

I had a baby in 1954 and it was born without skin over its stomach. It was at four in the afternoon and all of the livers and intestines were coming out. We took it to the hospital. The doctors said they had never seen that happen before. He died at one in the morning. The doctors took him and kept him to study him.

I paused to see the detachment in Janet’s fact as she told me this. It seemed to be an incident stored in her memory as an event that feelings were no longer connected to. I supposed this was a survival mechanism for Janet and as I sat there shocked and overwhelmed she urged me on with more stories.

It used to be very bad to have more than one baby at one time. You weren’t supposed to keep both, one was to be killed. In 1930 my Aunty had twins. She heard the other villagers talk about killing one of her babies so she ran way with her babies to Gauteng Province.

So people were afraid of twins?

Yes, in 1948, in my village a woman had triplets-all girls. No one had ever seen that and it was in the newspaper and the mom left with them. If she would have stayed they would have killed two of the babies. All three girls eventually got married and live in the next village over.

Is there anything else you can tell me about after the baby is born or feeding it?

After baby was born we used to rub on it a sour milk butter to help it grow. It smelled terrible…eish…I didn’t like to be near the baby when it smelled like that. We give the baby our breast for food. They usually take our milk until they are two years.

By now Janet had finished her coffee and I had my questions answered. I felt a deep connection with this woman, who like me was struggling to carve a place for herself in a world so drastically different from the one in which she had grown up. Her words compounded to give a visual picture to the idea that we all have our own stories and information and that each of us is worth communicating with and exploring.